Tracing Alberta’s Earliest Recorded Journey Using 3D Scanning Technologies

- 3dinfo2

- 6 hours ago

- 4 min read

In Southern Alberta, history is often hidden in plain sight. Hills, ridgelines, and creek beds that we pass every day once guided the earliest Indigenous communities, fur traders, and surveyors who mapped this part of the world long before roads existed.

Earlier this month, we had the chance to help document one such place, a site that may connect directly to the earliest written account of a European travelling deep into southern Alberta. The story starts in 1792 with a Hudson’s Bay surveyor named Peter Fidler and leads to a cluster of weathered rock formations east of Beiseker.

Local historian and Senior Project Archaeologist Brian Vivian (Lifeways of Canada), along with explorer and archaeological researcher Byron Smith (Calgary Explorers Club, Archaeological Society of Alberta), reached out after discovering a series of carved inscriptions they believe could be tied to this period. What they shared with us, and what we saw in the field, made it clear this location could hold rare physical clues from a formative moment in Alberta’s history.

That is where we came in.

Why This Site Matters: Peter Fidler’s 1792-93 Journey

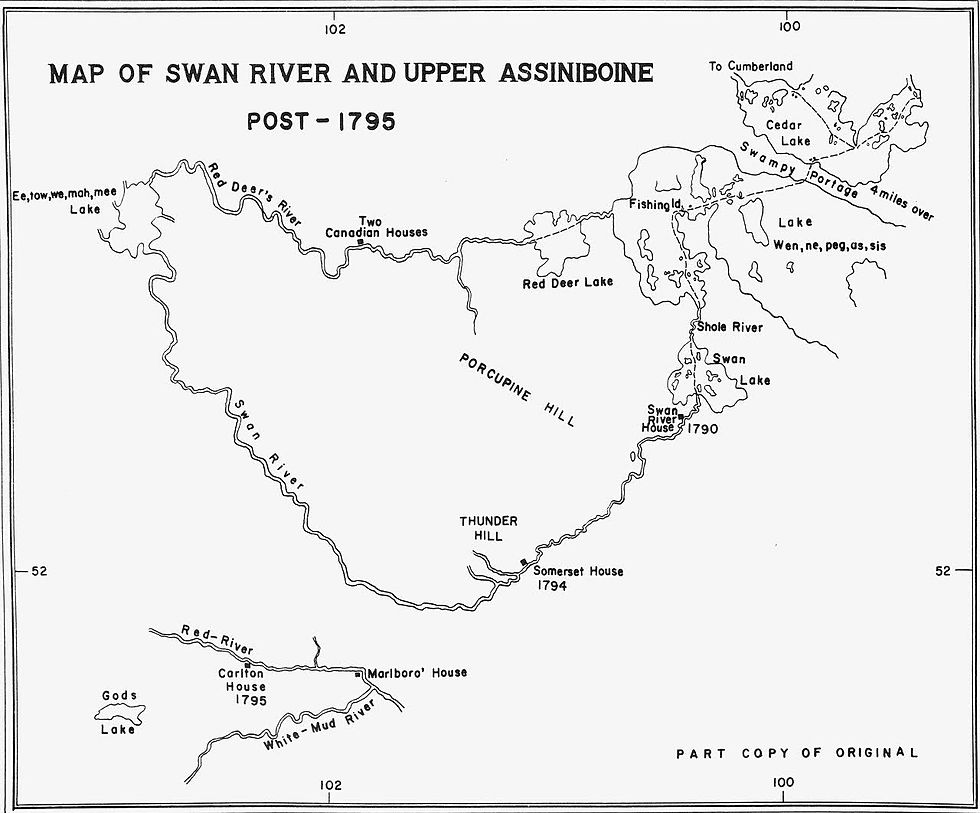

During this project, our team revisited the history behind the discovery with help from Brian and Byron. Their research points to a remarkable chapter from Fidler’s journals, specifically his trip from Buckingham House into southern Alberta in the winter of 1792-93. Guided by a small group of Piegan (Piikani) leaders, Fidler travelled farther south than any European recorded at the time.

His journals are unusually detailed, filled with descriptions of the Bow River, Red Deer River, Devil’s Head Mountain, Banded Peak and daily observations that now help historians retrace the route with surprising accuracy.

One entry stands out.

On December 5, 1792, Fidler wrote:

“At 9AM we resumed our Journey, & went SSE ½ E 5 miles & crossed a creek a little above, a high steep face of rocks on the East Bank of the Creek, which the Indians uses occasionally as the purpose of a Buffalo pound… perpendicular about 40 feet… vast quantities of Bones was laying there, that had been drove before the rock.”

This description is one of the earliest written accounts of a buffalo jump, a hunting method central to southern Alberta archaeology and exemplified by UNESCO-recognized sites like Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump.

Based on Fidler’s distances, peak sightings, and terrain notes, Brian and Byron believe the rock face they visited matches this location. The inscriptions scattered across the site may help illuminate who passed through here and when, whether Piikani hunters, early Hudson’s Bay Company traders, or travellers whose stories were never formally recorded.

The Discovery: Inscriptions Spread Across Four Rock Formations

The team initially believed there were around ten inscriptions. Once on site, that number grew to roughly fifteen, spread across four separate rock formations within a compact 30-square-metre area. The markings vary in depth, style, and weathering, suggesting different authors and periods.

Capturing them accurately was going to require a mix of coverage and precision. Outdoor conditions, uneven rock surfaces, and late-season weather added a few challenges.

But those are exactly the types of environments where portable, high-resolution 3D scanning shines.

How We Documented the Site

We planned the fieldwork around a forecasted break in the weather and met Brian and Byron at the site. Temperatures were just above freezing, workable but cold enough to make equipment choices important.

Equipment and setup

To cover the area and preserve every detail, we used two systems:

Creaform's HandySCAN EVO for high-resolution scans of individual inscriptions

Surphaser long-range scanner for broad coverage

Field Workflow

Here is how we approached it:

Survey the landscape and map the four rock formations.

Move formation to formation, scanning each inscription with the HandySCAN EVO at sub-millimetre resolution.

Capture the full area with the Surphaser, giving us a clean spatial framework.

Verify coverage on site to ensure no carving was missed.

Brian and Byron guided us through every marking, sharing archaeological context and insights from decades of fieldwork and exploration.

The combination of the two scanning systems gives historians a precise, permanent digital record that can be studied without erosion, lighting or physical access getting in the way.

What the Data Will Help Unlock

The intention behind the project goes far beyond documenting surface carvings. The scans may help historians and archaeologists:

Compare inscription styles and tool marks

Estimate relative age through weathering patterns

Align the site to Fidler’s recorded travel route

Cross-reference with other Hudson’s Bay Company expeditions

Build a clearer picture of early Indigenous and European movement in the region

Most importantly, these digitized surfaces will remain accessible for future analysis as techniques evolve. Researchers can test new hypotheses without risking damage to the formations themselves.

A Glimpse Into Alberta's Past, Captured in 3D

Projects like this sit at the intersection of archaeology, history and digital preservation. Standing at the base of that rock face, with wind cutting across the creek and the plains stretching out beyond, it is easy to understand why Fidler described the place in such detail. The natural features, the vantage points, the geography, it all lines up.

Whether the inscriptions ultimately connect to Fidler’s party, to earlier Hudson’s Bay traders such as James Gaddy, or to Indigenous hunters who used this buffalo jump long before European arrival, the site clearly holds stories worth telling.

We are grateful to support Brian and Byron in documenting this discovery, and we will continue working with them as the research unfolds. For now, the scans mark an important step in preserving a piece of Alberta’s early history, one rock at a time.

Comments